Warning: Undefined variable $k in /home/nginx/domains/wired2fishcom.bigscoots-staging.com/public/wp-content/themes/understrap-child-0.6.0/functions.php on line 984

Warning: Undefined variable $k in /home/nginx/domains/wired2fishcom.bigscoots-staging.com/public/wp-content/themes/understrap-child-0.6.0/functions.php on line 987

Walleye are highly sought after sportfish that are considered to be a delicacy to many anglers. But did you know that walleye were once considered to be two species or that they have been introduced throughout the U.S. to varying degrees of success? If this is news to you, you are about to learn a lot about walleye.

WALLEYE HISTORY

Walleye (Sander vitreus) belong to the Percidae family, including yellow perch, darters and saugers. Walleye are the largest members of the Percidae family in North America. Walleye are closely related to sauger (Sander canadensis), enough so that hybridization between the two is common. The resulting offspring is known as a saugeye.

Walleye were first described by Samuel L. Mitchill, a New York naturalist, physician and politician. Mitchill wrote about walleye and other species of fish of New York in “The Fish of New-York”. The genus name of walleye is Sander. Which refers to the German common name of a fish closely related to walleye in Europe called a zander (Sander lucioperca). The species name Viterus means glass or glassy, which refers to the eye of a walleye, which appears to be silvery or transparent when light reflects the eye.

At one time there was the belief that there were yellow walleye Sander virteus found in the majority of the natural home range and blue walleye Sander glaucus found in southern Ontario, Quebec and throughout the Great Lakes region. The blue walleye was classified as a species in 1926 then downgraded to a subspecies. In 1967, it was listed as an endangered species and by 1983 the blue walleye was believed to be extinct. DNA analysis from a frozen blue walleye revealed it was the same species as a yellow walleye with a phenotypic coloration difference, meaning they are all just walleye. Occasionally a blue walleye is still caught in Lake Erie, Ontario or the Ohio River.

Other Names for Walleye

The walleye has several nicknames: Ol’ Marble Eye, glass eye, yellow walleye, blue walleye, walleyed pike, yellow pike, grass pike, jack, perch pike and dory.

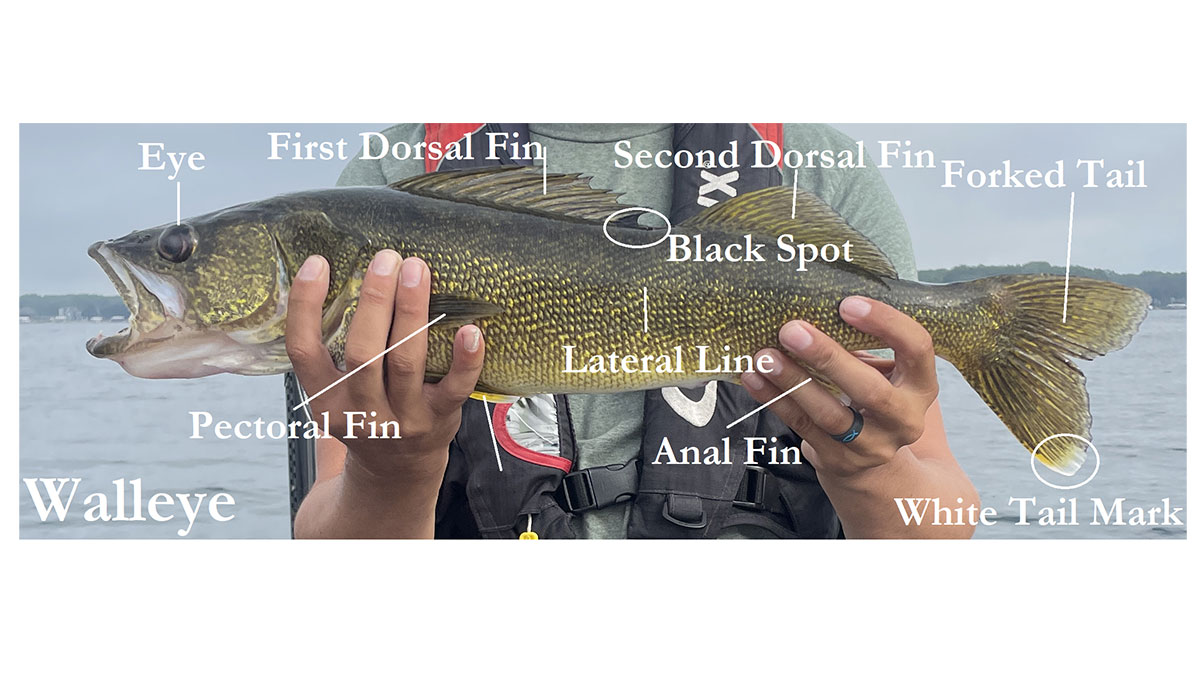

WALLEYE IDENTIFICATION

Walleye share many of the same characteristics as the Sauger and are often easily confused with one another. We are able to differentiate between the two by identifying the features associated with body shape, color and patterns, spiny dorsal fin and the caudal fin.

The body of walleye are relatively large, elongated with a nearly cylindrical shape. The upper-back region of the fish generally ranges in color from olive to yellowish brown with the stomach and lower abdomen regions being lighter in color. At times seven to nine darkened bars may be present in the form of back saddles that extend down the sides. Walleye have a complete lateral line that is unbroken all the way down to the caudal tail. Color brilliance can vary greatly depending on their geographic location, water conditions and water quality.

The dorsal fins on both walleye and sauger are transparent or lacking pigment, but the walleye will have a dark spot located on the back region of the spiny dorsal fin, whereas the sauger will have dark speckling covering the dorsal fins. The dorsal fins are widely separated and distinct. The caudal tail fin is forked with the tip and lower lobe of the tail fin having a white coloration. Walleye have 12 to 14 first dorsal fin spines and 1 to 2 second dorsal spins. They have 19 to 22 dorsal fin soft rays and 12 to 13 anal fin soft rays. The black dorsal spot and white tail tip are two very important distinguishing features compared to sauger.

The walleye will have a large, terminal mouth where the upper jaw extends to the middle of the eye. Within the mouth are strong, well-developed canine-type teeth within the jaw. The number and size of teeth vary but average between 30 and 40 total with length up to 1/2 inch. The teeth are spread apart and appear extremely sharp, however they are often blunt with a rounded tip.

WALLEYE LOCATION

Walleye naturally occurred throughout North America east of the rocky mountains, with the center of their U.S. distribution within the Great Lakes region and upper Mississippi River basin. Its northern boundary extended well into Canada with populations throughout Quebec and west up into the Northwestern Territory region. To the south, walleye stretched down into Arkansas and Alabama.

Walleye have been initially stocked outside of their home range for decades as a sportfish. This began in the mid 1870s with fish being transported from Vermont to California. Introductions continued throughout the west coast and south into Texas throughout the 1960s and continue today to a lesser extent. Walleye have also been introduced accidentally or illegally and impact minnow, perch and juvenile trout populations. Today walleye populations throughout the U.S. could be considered to be growing, due primarily to standing restocking programs to supplement sportfish populations.

Walleye have not been widely transported outside of North America for stocking, with exception of a possible stocking in China. The zander dominates the European areas covering a similar niche as walleye would, therefore limiting the desire to move walleye outside of North America.

To see the extent of the native and introduced range of walleye throughout North America we have created this interactive map.

WALLEYE SPAWNING

Both water temperatures and the time of the year play a significant role in initiating spawning activities. The majority of the spawning activity occurs at the end of March to the beginning of April and the farther north you go, the later the spawn happens.

Walleye are open-water spawners. They offer no parental care and devote no time or effort into nest building. Spawning begins with a short migration to areas of warmer water around 50 degrees fahrenheit; walleye will migrate back to their birth location for spawning if they are able to. They will select a relatively shallow area 1 to 10 feet, with rocky bottom and moderate waves or current. The water movement helps to keep the gestating eggs oxygenated and free from silt buildup.

Walleye will spawn in small groups with one to three females and two to six males. The small group will simultaneously swim to the surface releasing eggs and fertilizing them indiscriminately. This process typically occurs in low-light conditions, just before or after sunset. Once fertilized the current will carry the eggs slowly to the bottom where they will stick to the substrate. Eggs ripen on the substrate and hatch at 12 to 18 days depending on water temperature.

Female walleye will reach full maturity at four to five, while male walleye reach maturity at two to four. During the spawn, female walleye will carry 20,000 to 600,000 eggs depending on their size. Females deposit eggs over one single night of spawning, while males will fertilize several spawning attempts throughout a season. Once the eggs are laid, the females will migrate back to feeding locations while males continue to look for more spawning opportunities.

WALLEYE SIZE AND LIFESPAN

Fry walleye are born at .2 to .3 inches in length and are completely transparent. They will begin to swim up shortly after absorbing their yolk sac. The fry feed mainly on small zooplankton. But by 1 1/2 inches, walleye will develop the ability to consume fish, including other walleye fry. This early onset of carnivory is based on the growth of their canine teeth which allows them to capture prey earlier in life than many other species. In low density fish populations or low calcium environments foraging on fish can be delayed until walleye reach 3 inches.

The early switch to fish forage allows walleye to have rapid first year growth that trails off each year. There are distinct growth patterns associated with river versus reservoir populations, north versus south populations and males verse females with the same population. As a general rule, walleye found in southern climates or in reservoirs tend to have faster growth rates but shorter overall life spans compared to northern climates or rivers. .

Southern walleye have a growth rate of around 9 inches after the first year, an additional 6 inches in year 2, and 2 to 3 inches a year until they reach their maximum size. In northern reaches of the walleye’s range growth rate is around 7 inches after the first year and additional 5 inches in year 2, 3 inches in year 3, and 1/2 to 1 inch each year until they reach their maximum size.

Female walleye will almost always outgrow their male counterparts. They will have a slightly faster growth rate, averaging 1 to 2 inches a year more than males. They will have a larger maximum size averaging 30 inches compared to 25 inches for males. Females will also have a longer life span living 25+ years compared to 15 years for a male in the north and 8 to 10 years in the south. Males will typically mature one year before females and devote more of their year to spawning activities.

WALLEYE DIET

The cloudy, opaque eye of the walleye actually allows them to see in low-light conditions. They capture forage using their canine teeth but consume it whole. Walleye prey that escape often have teeth marks to show for their efforts. They hunt or stalk prey using their exceptional eyesight and are generally considered to be primarily a nocturnal fish.

Walleye are primarily carnivores, in the early life stages they feed mainly on zooplankton, insects and small invertebrates such as worms. This hones their feeding skills and allows them to develop that predatory mindset that they are so greatly known for. Once canine teeth develop, their diet shifts to an adult life diet, feeding increasingly on fish such as the yellow perch and crayfish. The early diet switch is extremely important to their rapid growth rates but it also leads to a great deal of cannibalism among year classes of walleye. As individuals that can switch more rapidly can often consume their siblings. Beyond their first year walleye feed primarily on fish or crayfish with almost all their feeding occurring at night.

Walleye are generally considered to be an extremely opportunistic fish. They will feed on just about anything they can fit in their mouth, sometimes this even leads to its own death due to larger prey like other walleye and bass getting stuck in its mouth. In introduced areas walleye have the ability to quickly decimate native minnow, darter and crayfish species, they will consume juvenile trout limiting the viability of stocking programs and offer great deal of competition to native predators. Their aggressive nocturnal feeding, large sensitive eyesight, canine teeth and overall body shape make them an extremely successful predator.

In order to fool walleye and catch them, I recommend reading Tim Allard’s tips on catching walleye. Tim has also created a comprehensive list of the best walleye baits on the market.

WALLEYE HABITAT

Adult walleye fit a pretty large narrative as far as the environment they can be found in and is dependent on time of day, water temperature, number of bait fish, etc. Their peak abundance throughout North America is centered around the Great Lakes region expanding further northward into central Canada. They can adapt to almost any river, reservoir or natural lake that has deep water refuge, current and abundant forage. Their reproductive success will vary greatly depending on their ability to dispearce eggs and water bodies ability to provide oxygenated water to the substrate. Once established, walleye will migrate slowly throughout river connections and build both river and reservoir populations.

Walleye are bentho-pelagic fish meaning they utilize both deep and shallow water to their benefits. During the daylight, walleye are generally benthic and stay in the deeper area of the water body. This allows the walleye to forage in low light conditions even during the day. During these benthic times walleye are often found in schools near structure. This structure could be some sort of rock, ledges, submerged trees, bridge pilings or around dams where the current is generally lower.

At night, walleye are pelagic which means they stay in the shallower areas of the water column sunlight typically is very intense for walleye. They move to these areas to feed on forage fish by taking advantage of their extremely efficient nighttime vision.

WALLEYE THREATS

Today through stocking programs, expanded range and harvest regulations walleye are fairly stable and experience only fishery specific population issues. Large flooding events, severe drought, loss of river connectivity and increase in reservoir fertility can cause major shifts in forage availability, egg survival and migration that limit the reproductive success of walleye. These events compounding over several spawning seasons coupled with the desire for anglers to harvest larger walleye can make populations sensitive to overfishing.

WALLEYE FACTS YOU NEED TO KNOW

- There is meat that can be harvested from the face of walleyes.

- The biggest walleye ever caught was in 1960 on Old Hickory Reservoir in Tennessee, weighing in at 25 lbs by angler Mabry Harper.

- The Walleye is named for its opaque, cloudy-looking eye. This is caused by a reflective layer of pigment called the tapetum lucidum.

- The oldest recorded walleye was 29 years old, weighed 25 pounds and was 107 centimeters (42 inches) long.

- Walleye are the state fish of Minnesota, South Dakota and Vermont.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Steven Bardin obtained his bachelor’s degree in Freshwater Biology from Tarleton State University in 2009 and his master’s degree in Fisheries Science from Texas A&M in 2013. While at Tarleton, Bardin worked for Harrell Arms at Arms Fish Farm and Bait Company. In 2011 he founded Texas Pro Lake Management. He strives every day to take a scientific approach to helping his clients maximize the production of their fisheries.

Outside of TPLM Bardin has written for Wired2fish, taught as an adjunct professor for Tarleton State University, and served as an instructor and camp coordinator for Bass Brigade youth leadership camp. In 2021, Bardin helped Major League Fishing found their Fisheries Management Division and leads their conservation efforts today.

Bardin is a member of Texas Aquatic Plant Management Society, Texas Chapter of American Fisheries Society, Southern Division of American Fisheries Society, Society of Lake Management Professionals, Texas Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame Board, Texas Brigades Board, Texas Freshwater Fisheries Advisory Committee and the Major League Fishing Anglers Association Board.

You can follow him on Facebook and Instagram.