It has unfortunately happened to all of us. No matter how experienced of an angler you are, every once in a while we all have a fish that gets hooked in the gill. Immediately we remove the hook and hope this doesn’t cause the fish any harm and that it doesn’t bleed. Fish bleeding tends to be a worst-case scenario for an angler and we thought we could answer a few questions about the best practices for an angler when they face a bleeding gill.

Wired2fish contacted me to learn more about a few things. First and foremost, they wanted to know the best practices to help a bleeding fish after being hooked in the gill. How long does it take a fish to recover? Finally, does pouring soda on a fish’s bleeding gills actually work?

I decided take it a step further and run a study to answer these questions. This is the story of both my study and findings.

Gill anatomy and operation

I wanted an answer to this question in as much detail as possible. My initial feeling is based on how a gill works, the best practice is to simply get the fish back into the water immediately.

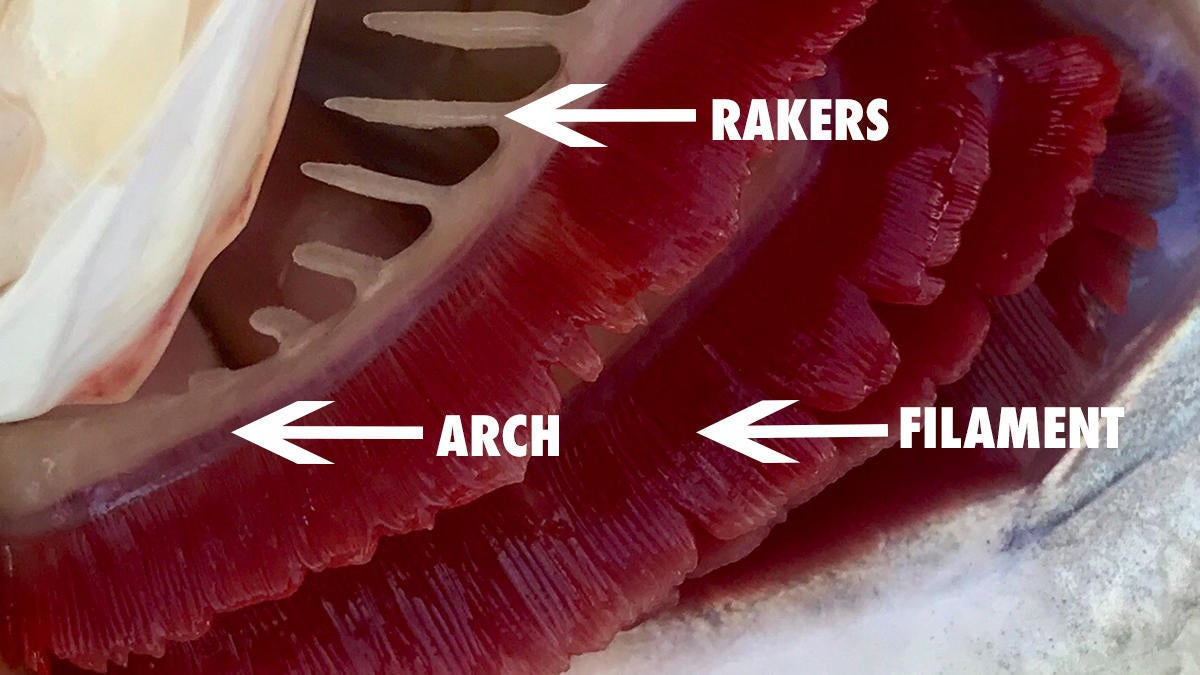

Gills are made of three main parts: The arch which is the central structure of the gill, the rakers which are positioned under the arch and protect the gill and the filament. The gill filament is the red-colored part where blood actually flows against the water that enters through the mouth.

This process is how fish pull oxygen from the water and release waste such as ammonia. This counter-current flow likely would stop any bleeding of the gill fairly quickly.

Study goals

I have heard of anglers attempting to stop the bleeding using various techniques before they release the fish. The method that intrigues us the most is the method of pouring soda onto the bleeding gill.

I didn’t plan to determine why the soda works; I would think it has to do to the sugar restricting the blood vessels. Instead, I wanted to focus on answering a simple question: Does pouring soda on a gill actually stop bleeding?

Also, not being a cellular biologist I didn’t look at the effects that soda might have on the long-term cellular morphology of the gill filament. Instead, I compared the recovery time between soda treated and non-soda treated fish.

Experimental design

I designed the experiment using three 10-fish treatment groups. All 30 fish were captured using electrofishing and measured between 12 to 14 inches. All 30 fish were sedated and randomly assigned a treatment group.

For group “A” I used a hook to create a laceration in the area where the gill arch meets filaments and applied no soda. For group “B” I used the same procedure to create a laceration then applied soda to the gill until the bleeding appeared to stop. Group “C” was the control group which were sedated but had their gills untreated.

Group “A” and “B” were marked using a unique fin clip to denote their treatment type and then all 30 fish were released into a .20-acre hatchery pond. The pond has been stocked with forage fish but no other predatory fish.

I used angling success to determine recovery. At 24 hours post-treatment, angling began in small 15 to 30-minute attempts to measure fish recovery based on successful recapture. Once recaptured, each fish was removed from the study and images were taken of the gill filament.

Results

Following laceration of the gill of treatment group “B” fish, soda was an effective method to stop bleeding. This was achieved using low volumes of soda; for the 10 treatment fish, a total of 30 ounces of soda was used.

Some lacerations did take two pouring attempts to completely stop bleeding. Interestingly enough, although sedated, every fish had a muscular reaction to the soda application. All fish released recovered from sedation except one treatment “B” fish (soda), which deceased.

On day one following the treatment, one group “A” fish (no soda) was captured via angling. The gill filament of this fish showed slight discoloration in the immediate area where the laceration occurred but appeared healthy in all other ways.

On day two at 48 hours post-treatment, four fish were captured via angling-two from group “A” (no soda) and two from group “B” (soda). None of these four fish had discoloration in gill filament around the laceration area.

Fish were recovered in both treatment groups “A” (no soda) and “B” (soda) on days three, four and five. Day five was the first day a group “C” (control) fish was recaptured. This trend continued over 14 days as all fish were recovered.

Conclusion

Based on this study and the angling results, I have come to several conclusions.

The best management practice for an angler who hooks a fish in the gill and causes bleeding is to use pliers to remove the hook and get that fish back into the water as quickly as possible.

If you prefer to use the soda trick, it appears to coagulate the blood and stop the bleeding but does not appear to improve recovery. We did use a single brand of citrus-flavored soda during the study and it would be interesting to determine if other brands had similar results.

This study was conducted in early spring conditions where water temperatures were stable between 58 to 65 degrees. At this temperature range, all fish appeared to recover and become catchable within 24 to 48 hours regardless of treatment group. The results would likely be different as water temperatures increased into the summer months.